* Ntibinyane Ntibinyane

Ten days ago, four days before Christmas day, my morning started like many others. I wanted to prepare breakfast for my kids—a simple magwinya (puff-puff) recipe, reminiscent of my childhood in Botswana, or something like savoury Timbits for those who need a Canadian comparison. But what should have been a delightful moment turned into a nightmare. Boiling oil splashed across my face, and immediately, like a boiled potato, my epidermis peeled away, sending everyone in my household into a panic. Within minutes I was rushed to the hospital in an ambulance, in excruciating pain, my skin exposed, raw, and burning with an intensity I had never experienced before.

I was admitted to the emergency unit, where I waited for about eight hours to see the doctor. When I finally did, the prognosis was sobering. My face was scarred, red, and unrecognizable. This is mostly a second-degree burn, they said. Healing, they warned, could be very slow, painful, and would possibly leave permanent marks. I resigned myself to the possibility of a long and challenging recovery. I left the hospital that day in haze of despair. As I walked down the hallways of the hospital with my family, strangers stared at me with a mixture of pity, curiosity, shock, and unease over my uncovered burn wounds.

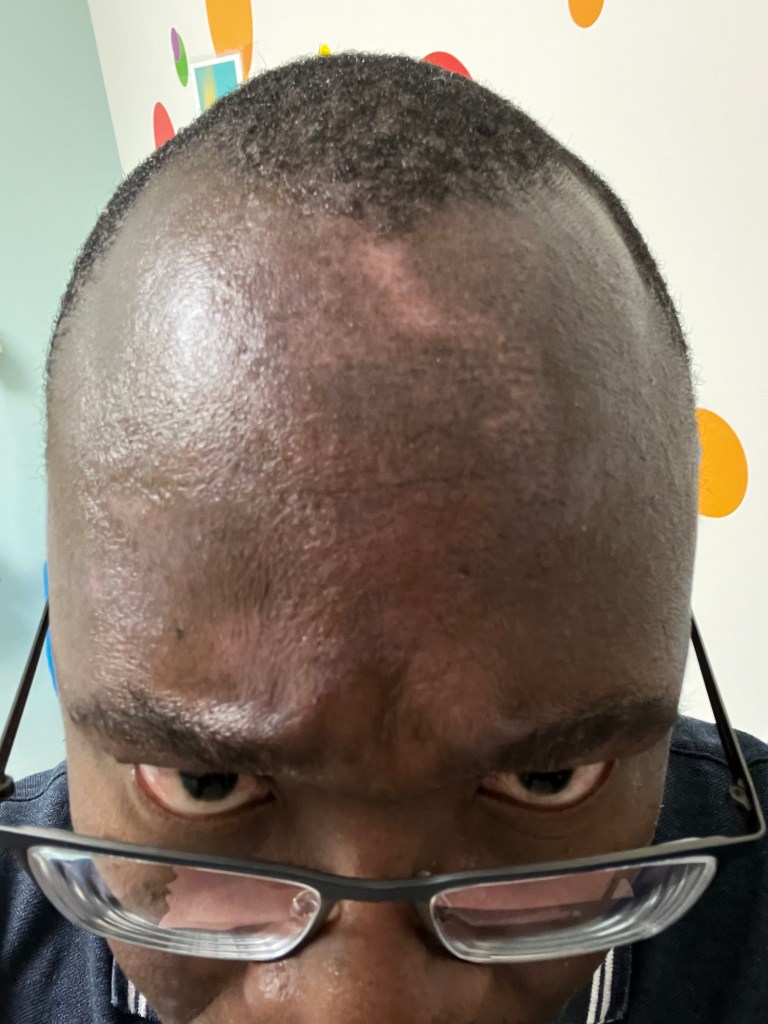

Ten days later, when I returned to the Acute Burn unit at University Hospital in Edmonton for a check-up, a kind nurse who had seen me on my first visit gasped in disbelief. “Wow?! This is unbelievable,” she exclaimed. “Do you see my jaws,” she said, gesturing to her open mouth, “they just dropped! I can’t believe this is the same face I saw just days ago.”

Can you believe it? In ten days, the redness was nearly gone, the raw patches had healed, and my melanin had regenerated, blending seamlessly with the rest of my skin. What had once been a scarred and painful surface now looked almost untouched, as if the trauma had never occurred. “What did you do?” the nurse asked. “Nothing,” I replied. “I applied moisturizing cream to keep the wounds moist as you suggested, and I also took some Vitamin A.” She later remarked, “In my 11 years working in this clinic, I’ve never seen a case like this. I know Black skin heals faster than White skin, but I never thought it would be this quick.” Her amazement was echoed by others in the unit, including my doctor and occupational therapist.

My recovery defied expectations, but it also sparked conversations in me about the remarkable properties of Black skin, something that I had not fully appreciated before this experience. While I had followed the simple recommended care routine, my swift healing wasn’t something anyone could fully explain. It left me marveling at my own biology, this Black skin, this melanin-rich shield that had endured so much trauma yet rebounded with such resilience.

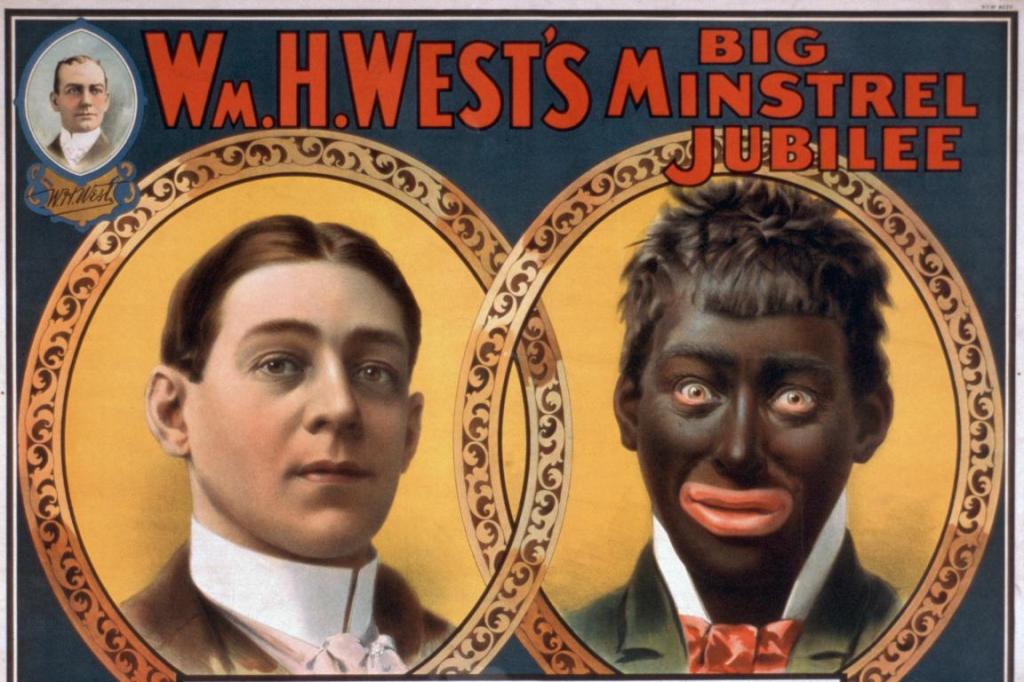

Black skin has always been more than just a physical attribute. It is a symbol of survival. It carries within it the history of a people who endured unimaginable hardships. The scars of whippings during slavery, the bruises inflicted by the fists of oppression, the wounds of colonial exploitation, the marks of racism and stereotypes, and, more importantly, the spirit of resilience and hope. Indeed, Black skin has been a site of pain yet also of profound healing. It regenerates not just on a cellular level but also symbolically.

Yes, I am reading too much into this, but I see my healing face as a metaphor for this resilience. In the same way, my skin began to regenerate and restore itself, Black communities have continually rebuilt and risen above all forms of injustices over the past 600 years. The melanin in my skin, which protected and hastened my recovery, mirrors the endurance of Blackness—a resilience rooted in biology, culture, spirit and faith.

Science provides part of the explanation for this resilience. I’m not a scientist, but according to research scientists, Black skin, with its high melanin content, is equipped to protect and heal itself in ways that lighter skin cannot. Melanin acts as a natural barrier, shielding the skin from ultraviolet rays and minimizing cellular damage. The compact and cohesive structure of the outermost layer of Black skin enhances its ability to retain moisture and resist external trauma. Collagen fibers, smaller yet denser, further contribute to its ability to heal with minimal scarring. It’s important, however, to recognize that these variations in skin properties are part of human diversity and not evidence of fundamental biological differences between races. These differences reflect adaptations to environmental conditions over time, not divisions of capability or worth.

However, this scientific understanding of Black skin contrasts starkly with the way it has been treated historically. For centuries, Black skin has been pathologized, detested, and scorned, seen as a mark of inferiority by systems built on exclusion and inequity. In the medical world, this history lingers. Studies show that Black patients often receive subpar care, with conditions like burns and rashes frequently misdiagnosed or undertreated. Medical textbooks and training materials still fail to include adequate representations of darker skin tones, leaving healthcare providers unprepared to address the unique needs of Black patients.

Yet, this same skin, my skin, so often misunderstood, has withstood centuries of scorn and exploitation. It has borne the lashings of colonialism, endured the violence of racism, and resisted attempts to erase its dignity. And like my face, it has healed—sometimes quickly, sometimes over generations, but always with a strength that defies expectation.

As I look in the mirror today and inspect every scar and every mark in my face, I see more than a face that is healing well. I see the strength of my African ancestors, the resilience of my identity, and the beauty of my Blackness. I see the work of God in me. For me, my recovery is not just a personal victory, it is a celebration of the power embedded in Black skin.

This skin, my skin, has endured oil burns, and it has also endured the burns of history. But just as my face has healed, so too have Black people found ways to heal from the wounds inflicted by oppression. And like my skin, we will continue to regenerate, to adapt, and to thrive. For me, Black skin is not just a surface, it is a story, a shield, a symbol of survival. And in its resilience, it carries a message and the message is: We are more than our scars. We are strength, beauty, and history in motion.

Leave a comment